Before I begin, I should note I'm not entirely sure what inspired me to write the forthcoming post. It probably has something to do with my feelings about politics and the greater discussion taking place at this most recently pertinent moment in American governance, the incumbent decision we're collectively soon to make. There's been a lot of discussion about Mitt Romney's first debate performance, which was exactly what the center-left feared it would be -- a very real opportunity for the GOP candidate to make his case to the American people as a credible candidate and to simultaneously and effectively cast the president in a bad light. Mission accomplished. We can discuss the reasons, but that doesn't really bear much mentioning. I will say the measured acumen of a politician more professorial in background is not conducive to a good show, debate wise. It's boring. It reminds people that our brains aren't designed to ruminate hard on anything. That our brains are instead designed for the quick flitting, downright thoughtless action needed to survive on a daily basis (see: Why Don't Students Like School? By Daniel T. Willingham). You don't ruminate much of your waking life about the things that surround you, at least not more than you take passing inventory of them for that reason I mention above. The point is, Mitt was all about survival, and if there's been one truly effective mantra of his campaign, it's been that as a businessman he is uniquely suited to helping America survive and then thrive again.

So what? Well, I got to thinking about my own self. Of coming to realize what kind of person I am. I never set out to write or be a "writer" when I was still a student in high school. Looking back on a letter I wrote to myself for a senior year English assignment, a letter addressed to me who is now 28, I asked about how my football career went, or perhaps was still going. A lot of hope in that. I can still almost feel the desire of my younger self, wanting to be in the NFL.

I am sorry to disappoint my younger self, too. I feel like if he had all the facts at the time, he'd be grateful for things working out how they have.

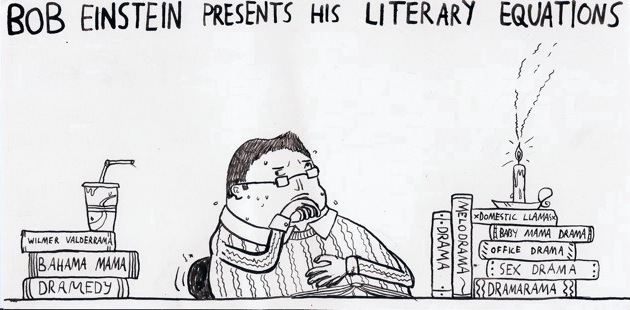

Thing is, while playing football I also liked writing very much. It was just more of a leisurely activity. I did it when I wasn't practicing, or weight training or otherwise prepping to be a football player. I wrote what I would have called satire then, a blanket term for anything humorous and possibly, possibly befitting of the true definition with some shred of sarcasm or irony, as well. It was at best a very raw skill I possessed. But that, along with drawing and reading were the seedlings of pastimes I found myself turning to more and more during my first year of college at Illinois State University, all with the hope of, as alluded to earlier, becoming an NFL player.

But it slowly became clear that I wasn't so cut out for the football grind. The practices were grueling and seemingly endless. I remember heading straight for the dining hall after getting out of the locker room and eating mass quantities of whatever was being served. And then the early morning practices I had through the entirety (it seemed) of the winter, when I'd wake up at 5am or so and put on my shoes to go run and train in nearby Redbird Arena with a number of my teammates and our strength and conditioning coach, who was, maybe by necessity, pitiless. You really didn't want to be late, ever, for any reason.

I remember one of my friends on the team describing his ultimate decision to quit in roughly this, very paraphrased, way: "I felt myself standing in the doorway of my dorm room, wavering back and forth. I said 'fuck this.' And I went back to sleep." I could relate.

There really was another problem during all of this, probably the most decisive of all. The coaches and I just didn't jibe. They were all (almost without exception) Oklahoma guys who'd gone to schools like OSU and Tulsa, one of them playing with the likes of Barry Sanders (or as he put it, jokingly, "Barry Sanders played with ME." This coach's most constant refrain was, "You don't like me, fight me," which sounds about right, no?) And to be fair, these guys weren't exactly bad guys, (they certainly weren't humorless authoritarians) but their worldview was at least a 180 turn away from where mine is today, and where I was headed at the time. I had leaned left politically since high school, after an especially memorable U.S. History course I took and friends of mine who'd made, and continue to make, exceedingly compelling points for the liberal cause.

It was likewise around my first year of college that I got interested in reading Al Franken, who was funny and political, who knew? (Much funnier, as I saw it, than his right-wing foes and foils.) I took a class on political history that was taught by Manfred Steger, a pretty well regarded authority these days on the effects of globalization. I was also excited to hear a lecture by Noam Chomsky who visited campus that year, fall '03.

Suddenly, I was by all rights a regular card-carrying communist.

I remember feeling like I didn't understand a lot of what Chomsky said at his lecture, but the parts I did, I agreed with. Chomsky was certainly no fan of President Bush. Because of my various influences, I certainly wasn't a fan, either. A year later, and mostly to my embarrassment and shame now, I was a rabid supporter of Michael Moore's polarizing documentary, Fahrenheit 9/11.

Some of my teammates who were in the same class as me, one of whom I definitely let read off my answer sheet during the final, that a coach had warned them about taking what Chomsky said too seriously, or at least reminding them to be skeptical. The coaches weren't "shades of gray" sorts of people. They were "cause and effect" sorts, who occasionally had to cram a round peg into a square hole.

I felt myself become that round peg. I wasn't fitting, no matter how hard they yelled. That's when I realized I was some kind of anomaly to them. I'm not saying I was ever given terribly much though, actually I think the opposite is true: I was written off. They equated smarts with football intelligence, and I was too unsure of myself to be that in their eyes. I remember toward the end of spring practices meeting with my position coach, the one who, if you didn't like him you could fight him, and having a candid conversation, most of which I don't remember. I do remember for one reason or another he left me alone in his office and I sneaked a look at the report on my skill development (all of this informed a big part of scene I've hitherto written into a story). It said things about my "good, quick feet, strength and flexibility" -- big positives for linemen -- but it also mentioned my failure to grasp their system, and that I would not be ready to play in the coming fall. When my coach returned, I figured I'd level with him and tell him that I'd been sort of struggling with some feelings of depression, which I was having trouble explaining. After my so saying, he looked at me as though I were an alien species. He didn't have much to say that was encouraging. I left with the feeling that I'd REALLY dampened his opinion of me, if it wasn't irrevocably the case already.

The last team meeting I attended, I felt like a stranger amid good friends who understood all of each other's inside jokes. It was raining outside. I was so desperate to get out of there. I also remember the disgust on my strength and conditioning coach's face when I told him I planned to workout at home over the summer, rather than spend it almost entirely on campus. I wanted out of there, as said. I got out of there and soon after realized I wouldn't be returning.

I got the sense from my experience at ISU that there are certain people who look at certain attributes in others as exclusively weakness, as though to save the body something's sometimes gotta be amputated. I was a bad football player largely because I was always second-guessing myself, not reacting to the play and just acting on instinct. When I'd played my best football in high school, my mentality was playing instinctively. The best football player is the one who just does. And the more unsure I got the worse my playing got. And it was abundantly clear there'd be no help coming to get me back on the right track. Maybe things could have been different at ISU, but I guess that's not my real concern in writing this, my real point. My real point is, while I felt the divide widen between myself and my coaches, I see them in retrospect, as the adults in the situation, doing more to widen it than anyone else. We were told by our head coach, "there are no atheists on our football team." I remember the defensive coordinator (one of the coaches I can say WAS humorless and actually, yes, a douche bag) in the midst of spring workouts telling me he thought I was "weak." Not in a motivating way, in a way that signaled his contempt.

I think we need to stop finding weakness in others, and instead determine where the true strengths reside. Are we really stronger with exclusion? With finding ways and means to tear down instead of build up? Certainly sometimes everyone needs a good kick in the pants and to stop feeling sorry for his or herself, but when do we know we've gone to far? And how do we get ourselves back on track when that happens? I tend to think with the support of each other, not the delight in besting a hated (or at least strongly disliked) enemy.

“Choose Hope or Despair”: On John Shoptaw

22 hours ago