Hey! Lookie here: I was invited to join pretty illustrious company recently by way of the forthcoming Hair Lit Anthology, a project masterminded by Nick Ostdick and Orange Alert Press. It's rad, bro. Totally. And while I don't know if hair metal dudes would be inclined to say "rad" or "bro," I'm sure this thing is going to be a good thing, enough to make them say "rad" and "bro" -- perhaps in spite of themselves.

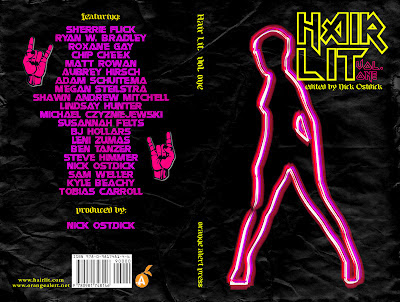

I mean check out this cover:

Rad, right?

You can help get this thing off the ground via a pretty nice kickstarter, one that -- depending on how much money you choose to put up -- could really produce some awesome prizes. Like the anthology itself plus a book by Roxane Gay, or Steve Himmer, or Michael Czyzniejewski, or Ben Tanzer or any of a number of other wonderful possibilities. So start the kick HERE.

I've also had a great month in terms of story publications. I have lived out certain dreams of mine. The first was having a piece in >kill author. I did that! In the very last issue of >kill author no less! Check it!

Then there was the second issue of Banango Street, which is awesome. I especially recommend Chad Redden's audio piece.

Then I was absolutely floored to be selected for SmokeLong Weekly by guest editor Laura Ellen Scott. I got to do a fun interview with her, too, which will come out when my story is released with the rest of the quarterly this fall. (AWESOME)

And lastly, KNEE-JERK! Knee-Jerk Magazine, which has recently undergone a site revamping. I had a little something with them, as well. Did I mention how much I love Knee-Jerk? I do!

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Sunday, August 26, 2012

Dinesh D'Souza: A Modern Right-Wing Intellectual?

There are a lot of right-wing intellectuals out there these days, just as there are those of the left. Avik Roy of Forbes and many other prestigious publications as well as a healthcare adviser to Mitt Romney; Dr. Charles Krauthammer, a well know face of modern conservatism (I grew up reading his syndicated column in the Chicago Tribune, and while rarely agreeing with his politics, I can acknowledge he's more than able to formulate a rational argument); Rich Lowry of the National Review, who took an admirable stand against those who defended George Zimmerman in the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting (under the unironic headline: "Al Sharpton Is Right"), and his famously severing National Review ties with John Derbyshire for what many considered an overtly racist article the latter wrote for Taki's Magazine. (I might also mention Jonah Goldberg, another National Review writer who'd be viewed more favorably by me if not for his ideologically bound Liberal Fascism, a book I really can't easily get past for a lot of its specious to out-and-out mendacious claims.) With all those listed I would say there's no doubt in conversation we'd disagree far more than we ever agree. But I respect where they're coming from generally, and for their courage to not always toe the party line, or to say things out of keeping with it.

Despite his Ivy-League credentials and an undoubtedly knowledgeable manner, the same really can't be said of Dinesh D'Souza. An ideologue's ideologue, who apparently has decided to become the right-wing equivalent of Michael Moore by way of his highly partisan documentary, 2016: Obama's America. I had no idea this movie existed until just this past weekend, when I came upon a Facebook friend's comment about it. The premise is really unreal. Where Moore's documentary implied some complicity, either directly or indirectly, by the Bush administration in the events of 9/11 D'Souza's cryptically pronounces Obama as having a secret agenda built upon the aspirations of his "socialistic" birth father, with whom the president it ought to be said barely had a relationship, meeting with Obama only once in his lifetime. Now I'm sure the film addresses their relatively non-existent relationship, maybe in the same way The Dark Knight Rises resolves SPOILER ALERT the relationship between Ra's al Ghul and his daughter, Talia. I don't pretend to know. But I do know it's unlikely to have much more than the most tenuous grip on the facts. And that has more to do with the one from whom its source material is derived, D'Souza himself. D'Souza has long beguiled me with his claims that liberal America must own its fair share of the blame for the 9/11 attacks. Of course he'll repeatedly point to the Shah of Iran's losing support from the Carter administration. What he's less wont to note is it was American and European intervention that foisted the Shah to authoritarian rule in the 1950, and it's also far more likely the ones who own that blame are the corporations who were unhappy with the elected government's nationalizing Iranian oil fields. That tidbit doesn't jibe well with D'Souza's very purposeful and, yes, very unfair message. I'd watch the movie if I thought it would give me any more but the same from this unabashed ideologue. Sadly, it's been and will continue to be very popular with his target demographic (sigh). Please, though, enjoy Stephen Colbert satirizing the hell out of D'Souza's unreasonable beliefs on the Colbert Report circa 2007:

Despite his Ivy-League credentials and an undoubtedly knowledgeable manner, the same really can't be said of Dinesh D'Souza. An ideologue's ideologue, who apparently has decided to become the right-wing equivalent of Michael Moore by way of his highly partisan documentary, 2016: Obama's America. I had no idea this movie existed until just this past weekend, when I came upon a Facebook friend's comment about it. The premise is really unreal. Where Moore's documentary implied some complicity, either directly or indirectly, by the Bush administration in the events of 9/11 D'Souza's cryptically pronounces Obama as having a secret agenda built upon the aspirations of his "socialistic" birth father, with whom the president it ought to be said barely had a relationship, meeting with Obama only once in his lifetime. Now I'm sure the film addresses their relatively non-existent relationship, maybe in the same way The Dark Knight Rises resolves SPOILER ALERT the relationship between Ra's al Ghul and his daughter, Talia. I don't pretend to know. But I do know it's unlikely to have much more than the most tenuous grip on the facts. And that has more to do with the one from whom its source material is derived, D'Souza himself. D'Souza has long beguiled me with his claims that liberal America must own its fair share of the blame for the 9/11 attacks. Of course he'll repeatedly point to the Shah of Iran's losing support from the Carter administration. What he's less wont to note is it was American and European intervention that foisted the Shah to authoritarian rule in the 1950, and it's also far more likely the ones who own that blame are the corporations who were unhappy with the elected government's nationalizing Iranian oil fields. That tidbit doesn't jibe well with D'Souza's very purposeful and, yes, very unfair message. I'd watch the movie if I thought it would give me any more but the same from this unabashed ideologue. Sadly, it's been and will continue to be very popular with his target demographic (sigh). Please, though, enjoy Stephen Colbert satirizing the hell out of D'Souza's unreasonable beliefs on the Colbert Report circa 2007:

| The Colbert Report | Mon - Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Dinesh D'Souza | ||||

| www.colbertnation.com | ||||

| ||||

Sunday, August 12, 2012

Debating Ignorance On The Internet And Specifically Facebook

Hey, you! Wow. You'd think after all the time I spent in my early twenties tied up in the inanity of political discourse on the internet I'd have learned some lesson, right? Wow, no, apparently I haven't yet. It'd be nice to, some day. I'm actually all for discussion of the issues. And granted it's hard to discuss the issues when memes like the following are being widely disseminated:

I know I should find better things to waste my time on, and there are equally specious pro-Obama memes are out there, floating around, cluttering the discourse, too. I know that. Still, I wanted to talk about Ronald Reagan, hero of the right. And yes, I came from the perspective that his presidency wasn't as great as this meme implies. And so I called upon his trumpeting of "Are you better off now than you were four years ago?" which at least subtly suggests blame for society's problems on his opponent, Jimmy Carter, during the 1980 campaign; his penchant for falling asleep during cabinet meetings (I hear this excused as, "probably got more done sleeping than Carter did awake." and other such noise that I'd prefer not to delve into); his love of a short workday; his taking twice as much vacation in the same time span as Obama (though one president definitely gets more grief for it); and his -- I'll concede -- probably unknowing complicity, or "actual deniability" as I believe John Poindexter once called it (instead of the more aware "plausible deniability"), concerning The Enterprise and sending armaments for money from Iran to the Nicaraguan Contras, during the Iran-Contra scandal. There's more, naturally. Any president can be accused of just as many gaffs as they can successes, and as always, it all comes down to perspective. Anyway, I went there. And it was bad. It was not a lot of name calling, at least between me and my most specific debate partner. But it was a waste of time.

We got nowhere.

For every reasonable point I made, my opponent felt the same way about his counterpoint. It just sort of went on like that, fruitlessly. To end it, I blocked the discussion. To further end these sorts of issues from coming up again, I deleted the person who'd originally posted the meme. Is that wrong? I'm inclined to say no. I say that because I did not know this person, a received-at-random add from him for reasons that remain mysterious to me, especially when if I recall correctly I came in contact with him for the first time while arguing in another thread with just the same sort of leftist bent.

What it comes down to are salient differences in belief. I'm at least largely a demand sider as goes economic theory, and I consider supply side economics very hazardous at best (a la the Clinton administration's bestowing "Most Favored" nation status onto trading partner China and the problematic and still controversial implementation of The North American Free Trade Agreement, which each decision made it more appealing to move American jobs overseas). A vehement supply sider would see my opinion in this regard as a wrongheaded, unnecessary restriction on the mechanisms of the global market. Simply put, don't make it harder to buy and sell (and produce) goods in other locations abroad. And as time has gone on we've been able to see the longterm effects, which have been largely good for corporations and the very wealthy, but like a lot of international commerce, much less desirable for the less wealthy on down. Thus the irony of the "Trickle Down" theory's name, which seems to have gotten stopped up somewhere as wealth continues to be increasingly consigned to the highest levels of American society to the detriment of all those (and not just the poorest) below them.

But often these components aren't reasonably looked at. And the individual he sees things in terms of his self, as we all do to lesser or greater extent, evaluates progress only by how good his/her life is, purely anecdotal and ego-centric terms, bordering at times on the solipsistic and, even, occasionally, the sociopathic. Which is why arguments can be so reductive. And suddenly name calling arises out of what was once a logical and reasoned debate. The party that is categorically wrong is usually the first to invoke derision. See: the history of racism, of subjection, of scapegoating and genocide. Meanwhile, how are we looking at the true merits of our sociological problems? I had a fascinating email exchange with Professor Robert Lopez of California State University-Northridge on this recent article he wrote for The Witherspoon Institute, and which tells a different story from the commonly held arguments supporting gay parenting. (Lopez himself was raised predominantly by his mother and a woman she became involved with, and he speaks of what he viewed as "being strange," in the eyes of the greater community around him, and likewise feeling strange himself.) Granted, I wrote to him because I wanted to determine where his and my own views intersected, but our views hardly completely intersect, even after discussing the matter with him more personally. Still, it was a very polite exchange, one that I feel good about and suggests to me that people on the opposite sides of any of the political perspective (on all the different issues) can, indeed, be debated reasonably. This is not something usually found on Facebook, however, and I think that's the lesson I want others to take from what I'm writing here. Don't be like me. Probably, where Facebook is concerned, you should leave well enough alone.

Yeah.

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Romney's "Culture" And Things Worth Keeping In Mind

Oh messy politics. Here we've been going, constantly. It's an unpleasant business, the American political landscape and all that's tied to it. I really dislike it. I wish it were cleaner and more positive. I'd prefer we all fall into our respective camps of belief, follow the credo invoked by many a Republican of an individual's right to personal liberty -- although that seems to be not without a few caveats regardless of the political persuasion of whoever's invoking the term.

Ostensibly, if you're a stereotypical Republican you believe "personal liberty" refers to one's right to own as many firearms as you choose to (and as much ammo to power those arms as you choose, likewise), freedom of Christian religion to be plastered everywhere you deem it's needed (i.e. everywhere), and freedom to hate the poor for choosing poverty (and gays for choosing to be gay). That, rather glibly, sums them up, right?

Conversely, if you're a stereotypical Democrat you believe in "personal liberty" to the extent that it doesn't offend others (and frankly, I get that and agree; but Steve Carell didn't just invent Michael Scott from nothing, the character came from alarmingly real source material; some people just don't understand how what they say is offensive, a consortium that -- like it or not, free and considerate speech advocates -- will always be part of the discourse). And Democrats will retain their right to be offended, sometimes adequately in proportion and sometimes less than adequately (Republicans often resort to the very same, in cases that usually begin with a Republican saying something offensive and not liking the response). The point is, Democrats dislike and often react poorly to a bigot's invocation of personal liberty. Democrats are also often guilty of hubris -- of being the know it all that thinks (s)he knows it all, but nobody does. And they could absolutely learn somethings from their Republican counterparts if they would likewise learn about them, and why Republicans see the country in the terms they do.

(If you haven't yet guessed, I'm more sympathetic to Democrats than Republicans. And when I cite each party affiliation I'm referring primarily to the people, the masses, who claim them as their ideologies of choice and not the politicians, who are usually far more similar than they are different.)

The problem consistently becomes one of unwillingness (or perhaps outright inability) to even attempt to understand another person's perspective. I try to imagine the notion of culture as, perhaps, Mitt Romney intended when he made the rather glaring mistake of identifying the difference between Israel and Palestine as one of "culture." I've seen the closeness of tight-knit rural communities firsthand. People in these places would bend over backwards for those whom they love and believe they can trust. And what's the best way to delineate whom you can trust from whom you cannot? How alike are they to you? Difference, just as an evolutionary consideration, can mean danger, can mean harmful, can upset a balanced ecosystem. It doesn't change the fact that by and large, in this day and age, we have little to fear from that historical Other. People are people, some are not ones with whom you'd like to be close, and others are. But there simply is no superficial set of criteria on which to base this decision. Romney couldn't have failed to notice the general differences between the average Palestinian and the average Israeli. Certainly, even if distinction by skin color isn't quite so easy in the Middle East as it was in the Jim Crow South, there are other superficial means. Though it wasn't always true, Americans are much more comfortable with Orthodox Jewish dress than they are typically with, say, an Orthodox Muslim's. You can see how someone of Romney's unarguably insulated background would find it easier to identify points of common interest among a largely Jewish population than a largely Muslim population, and that's without even addressing all the weight of generations of socio-political distinction between the two closely linked nation states (although one is not recognized as a sovereignty by the United States; I'll let you guess which one).

Fareed Zakaria is correct. At its most simplistic, the difference between these two regions is capitalism. Moreover, we must understand the distinction between Israelis and Palestinians is simply far more complex and far more monetarily attributable than some dubious notion of superior "culture" -- a term which to me might as well be referring to superior race. Culture has become the new, veiled term for previous and more overt labels.

What is it about human nature that on the one hand aspires to achieve so much and on the other lazily attempts to categorize self from others by facile determination? Blacks are intellectually inferior for some reason that was (and still is) conveniently and most enthusiastically put forth by White people. Why not let people become who they can become, before deciding that ahead of time? Plainly put, why do we aspire to achieve so much but constantly resort to some lazy, simplistic analysis of our fellow people? And why not understand that more often than not individual success is the product of community? Community on a wider scale could have a tremendously positive effect. That infrastructure is a good thing. That the poorest members of society should be protected from oligarchs. But don't take my word for it, as Adam Gopnik over at the New Yorker has extensively delved into, what were capitalism's preeminent founder Adam Smith's thoughts on the nature of labor and employer? How about this from Smith's seminal work, The Wealth of Nations:

I anticipate I might get comments about how government impedes this relationship, that it's the government and high rates of taxation that prevent employers from being more equable with wages. But how can we believe that, at this point? And what's more, even if you consider that the rate of corporate profit has finally begun to decline, for the first time since 2008!, they're still at a "paltry" 6.4 billion. The NY Times article further notes that the downturn has more to do with foreign markets than with domestic ones, something worthwhile to keep in mind.

I mean, isn't having a solid infrastructure across all strata of society desirable? For everyone?

Ostensibly, if you're a stereotypical Republican you believe "personal liberty" refers to one's right to own as many firearms as you choose to (and as much ammo to power those arms as you choose, likewise), freedom of Christian religion to be plastered everywhere you deem it's needed (i.e. everywhere), and freedom to hate the poor for choosing poverty (and gays for choosing to be gay). That, rather glibly, sums them up, right?

Conversely, if you're a stereotypical Democrat you believe in "personal liberty" to the extent that it doesn't offend others (and frankly, I get that and agree; but Steve Carell didn't just invent Michael Scott from nothing, the character came from alarmingly real source material; some people just don't understand how what they say is offensive, a consortium that -- like it or not, free and considerate speech advocates -- will always be part of the discourse). And Democrats will retain their right to be offended, sometimes adequately in proportion and sometimes less than adequately (Republicans often resort to the very same, in cases that usually begin with a Republican saying something offensive and not liking the response). The point is, Democrats dislike and often react poorly to a bigot's invocation of personal liberty. Democrats are also often guilty of hubris -- of being the know it all that thinks (s)he knows it all, but nobody does. And they could absolutely learn somethings from their Republican counterparts if they would likewise learn about them, and why Republicans see the country in the terms they do.

(If you haven't yet guessed, I'm more sympathetic to Democrats than Republicans. And when I cite each party affiliation I'm referring primarily to the people, the masses, who claim them as their ideologies of choice and not the politicians, who are usually far more similar than they are different.)

The problem consistently becomes one of unwillingness (or perhaps outright inability) to even attempt to understand another person's perspective. I try to imagine the notion of culture as, perhaps, Mitt Romney intended when he made the rather glaring mistake of identifying the difference between Israel and Palestine as one of "culture." I've seen the closeness of tight-knit rural communities firsthand. People in these places would bend over backwards for those whom they love and believe they can trust. And what's the best way to delineate whom you can trust from whom you cannot? How alike are they to you? Difference, just as an evolutionary consideration, can mean danger, can mean harmful, can upset a balanced ecosystem. It doesn't change the fact that by and large, in this day and age, we have little to fear from that historical Other. People are people, some are not ones with whom you'd like to be close, and others are. But there simply is no superficial set of criteria on which to base this decision. Romney couldn't have failed to notice the general differences between the average Palestinian and the average Israeli. Certainly, even if distinction by skin color isn't quite so easy in the Middle East as it was in the Jim Crow South, there are other superficial means. Though it wasn't always true, Americans are much more comfortable with Orthodox Jewish dress than they are typically with, say, an Orthodox Muslim's. You can see how someone of Romney's unarguably insulated background would find it easier to identify points of common interest among a largely Jewish population than a largely Muslim population, and that's without even addressing all the weight of generations of socio-political distinction between the two closely linked nation states (although one is not recognized as a sovereignty by the United States; I'll let you guess which one).

Fareed Zakaria is correct. At its most simplistic, the difference between these two regions is capitalism. Moreover, we must understand the distinction between Israelis and Palestinians is simply far more complex and far more monetarily attributable than some dubious notion of superior "culture" -- a term which to me might as well be referring to superior race. Culture has become the new, veiled term for previous and more overt labels.

What is it about human nature that on the one hand aspires to achieve so much and on the other lazily attempts to categorize self from others by facile determination? Blacks are intellectually inferior for some reason that was (and still is) conveniently and most enthusiastically put forth by White people. Why not let people become who they can become, before deciding that ahead of time? Plainly put, why do we aspire to achieve so much but constantly resort to some lazy, simplistic analysis of our fellow people? And why not understand that more often than not individual success is the product of community? Community on a wider scale could have a tremendously positive effect. That infrastructure is a good thing. That the poorest members of society should be protected from oligarchs. But don't take my word for it, as Adam Gopnik over at the New Yorker has extensively delved into, what were capitalism's preeminent founder Adam Smith's thoughts on the nature of labor and employer? How about this from Smith's seminal work, The Wealth of Nations:

He [the laborer] supplies them [the employer] abundantly with what they have occasion for, and they accommodate him as amply with what he has occasion for, and a general plenty diffuses itself through all the different ranks of society.

I anticipate I might get comments about how government impedes this relationship, that it's the government and high rates of taxation that prevent employers from being more equable with wages. But how can we believe that, at this point? And what's more, even if you consider that the rate of corporate profit has finally begun to decline, for the first time since 2008!, they're still at a "paltry" 6.4 billion. The NY Times article further notes that the downturn has more to do with foreign markets than with domestic ones, something worthwhile to keep in mind.

I mean, isn't having a solid infrastructure across all strata of society desirable? For everyone?

Labels:

Adam Gopnik,

Adam Smith,

Mitt Romney,

The Wealth of Nations

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)